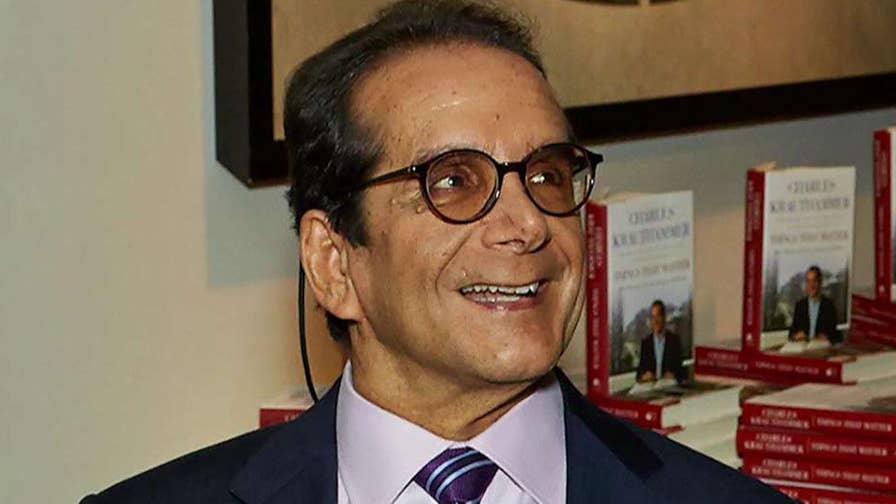

Charles Krauthammer, a longtime Fox News contributor, Pulitzer Prize winner, Harvard-trained psychiatrist and best-selling author who came to be known as the dean of conservative commentators, has died. He was 68.

His death had been expected after he wrote a heartbreaking letter to colleagues, friends and viewers on June 8 that said in part “I have been uncharacteristically silent these past ten months. I had thought that silence would soon be coming to an end, but I’m afraid I must tell you now that fate has decided on a different course for me…

“Recent tests have revealed that the cancer has returned. There was no sign of it as recently as a month ago, which means it is aggressive and spreading rapidly. My doctors tell me their best estimate is that I have only a few weeks left to live. This is the final verdict. My fight is over.”

In recent years, Krauthammer was best known for his nightly appearance as a panelist on Fox News’ “Special Report with Bret Baier” and as a commentator on various Fox news shows.

Following the news of the death of his “good friend,” Baier posted on Twitter, “I am sure you will be owning the panel discussion in heaven as well. And we’ll make sure your wise words and thoughts – your legacy – will live on here.”

Brit Hume, senior political analyst on Fox News, also tweeted about the “terribly sad news.”

“The great Charles Krauthammer has died,” he said.

But Krauthammer was arguably a Renaissance man, achieving mastery in such disparate fields as psychiatry, speech-writing, print journalism and television. He won the Edwin Dunlop Prize for excellence in psychiatric research and clinical medicine. Journalism honors included the Pulitzer Prize for Commentary for his Washington Post columns in 1987 and the National Magazine Award for his work at The New Republic in 1984. His book, “Things That Matter: Three Decades of Passions, Pastimes and Politics,” instantly became a New York Times bestseller, remaining in the number one slot for 10 weeks, and on the coveted list for nearly 40.

Krauthammer delivered his views in a mild-mannered yet steady and almost philosophical style, befitting his background in psychiatry and detailed analysis of human behavior. Borrowing from that background, Krauthammer said in 1990, after the fall of the Berlin Wall, that the post-Cold War world had gone from bipolar to “unipolar,” with the United States as the sole superpower. He also coined the term “The Reagan Doctrine,” among others.

Krauthammer harbored no compunction about calling out those in power, whether they were Democrats or Republicans or conservatives.

During the Democratic National Convention, he assailed lack of substance in the build-up to nominating Hillary Clinton.

“As for the chaos abroad, the Democrats are in see-no-evil denial. The first night in Philadelphia, there were 61 speeches. Not one mentioned the Islamic State or even terrorism.”

“In this crazy election year, there are no straight-line projections,” he noted, adding presciently, “As Clinton leaves Philadelphia, her lifelong drive for the ultimate prize is perilously close to a coin flip.”

At the same time, Krauthammer was quick to express disagreement with President Donald Trump in no uncertain terms.

He denounced Trump’s handling of the violence that erupted at Charlottesville, Va. protests over the planned removal of a Robert E. Lee statue, saying that most Americans were “utterly revolted by right-wing white supremacist neo-Nazi groups.” Krauthammer said that Trump’s failure to strongly denounce the supremacist group, and to say that both sides in the protest shared blame, “was a moral disgrace.”

The man who wore many hats, figuratively, throughout his life — excelling at just about everything he tried, even when he was still a rookie — easily took himself in new directions when curiosity or instinct struck.

Krauthammer’s intellectual heft belied an ability to be candid and witty about his quirks.

“Everything I’ve gotten good at I quit the next day to go on to do something else,” he quipped in a 1984 interview with The Washington Post.

Krauthammer embraced a strong personal constitution that kept him determined and resilient, even in the face of extraordinary physical limitations.

He spent most of his life confined to a wheelchair, the result of a snap decision — when he was 22 years old and a first-year student at Harvard – to go for a quick swim with a friend before a planned game of tennis.

“We go for a swim, we take a few dives and I hit my head on the bottom of the pool,” he said in a Fox News special in 2013 that looked at his life. “The amazing thing is there was not even a cut on my head. It just hit at precisely the angle where all the force was transmitted to one spot…the cervical vertebrae which severed the spinal cord.”

Unable to move, and at a time when his studies happened to focus on the spinal cord, Krauthammer instantly knew the consequences of the accident would be severe.

“There were two books on the side of the pool when they picked up my effects,” he recalled. “One was ‘The Anatomy of the Spinal Cord’ and the other one [was] ‘Man’s Fate’ by Andre Malraux.”

A lifelong opponent of being stereotyped in any fashion, Krauthammer was not going to let being in a wheelchair define him.

“I don’t like when they make a big thing about it,” he told the Washington Post. “And the worst thing is when they tell me how courageous I am. That drives me to distraction.”

“That was the one thing that bothered me very early on,” Krauthammer said. “The first week, I thought, the terrible thing is that people are going to judge me now by a different standard. If I can just muddle through life, they’ll say it was a great achievement, given this.”

“I thought that would be the worst, that would be the greatest defeat in my life — if I allowed that. I decided if I could make people judge me by the old standard, that would be a triumph and that’s what I try to do. It seemed to me the only way to live.”

As soon as he could after the accident, Krauthammer forged ahead with his studies, finishing medical school and going on to do a three-year residency at Massachusetts General Hospital, where he wrote about a condition he called “secondary mania,” which gained wide acclaim.

Then Krauthammer realized his heart was not really in health care, and after going to Washington D.C. and making some connections, he ended up as a speech writer for Democrat Walter Mondale during Jimmy Carter’s re-election campaign.

Later, as a writer for The New Republic, Krauthammer, then a self-styled Democrat, exhibited the kind of willingness to criticize political leaders regardless of their party.

“I’m very unhappy with the Democratic foreign policy,” he told the Post. “And I’m very unhappy with Republican domestic policy.”

“If I have to choose between Republican foreign policy and Democratic foreign policy I would choose the Republican. That’s not to say there’s a lot in it I don’t find wrong, but they have done certain good things in foreign policy.”

About a decade ago, Krauthammer joined Fox News, drawing praise from conservatives, moderates, and liberals for his thoughtful and meticulously framed remarks.

New York Times columnist David Brooks called him “the most important conservative columnist.”

When his book became a fixture on the New York Times bestseller list, Newsweek observed: “To those who are trying to make sense of the rise of the conservative movement, Krauthammer’s success is a triumph for temperate, smart conservatism.”

Krauthammer politely downplayed the accolades.

“I don’t know if I have influence,” he was quoted as saying in Michellbard.com. “I know there are people who read me and people who make decisions who read what I write and they may be affected…my role is to challenge them, but people don’t come up to me on the street and say ‘I used to be a liberal until I read you.’”

“My goal is to write something parents will clip and send to their kids in college.”

Charles Krauthammer was born in New York in 1950, and grew up in Montreal, steeped in the Jewish faith.

His father, Shulim Krauthammer, was Austro-Hungarian and his mother, Thea, was born in Belgium. His parents met in Cuba.

Before going to Harvard Medical School, Krauthammer attended McGill University, and Oxford, where he met his wife, Robyn.

They had a son, Daniel. Both his wife and son survive him.

Despite his busy professional life, Krauthammer enjoyed baseball and chess, and made his family a priority.

He often spoke of growing up in a happy, tight-knit family, and spoke proudly of his wife and son.

Leave a Reply