Although the federal government’s retention of Utah State lands is an extremely important and timely issue, let me be the first to admit that if we get too deep into the details and minutia of the legalities involved, eyes can easily begin to gloss over. In fact, all technical legal issues can have that effect on us—and I am no exception. The incalculable hours I’ve spent digging through piles of research that backs one legislative opinion or another cannot be esteemed as ‘golden.’ Yet, on this particular subject—the federal government’s failure to release the State lands temporarily ceded to it during the Western States’ admission to the Union—there is too much at stake to simply roll over and count it as a lesson learned at the hands of the neighborhood bully.

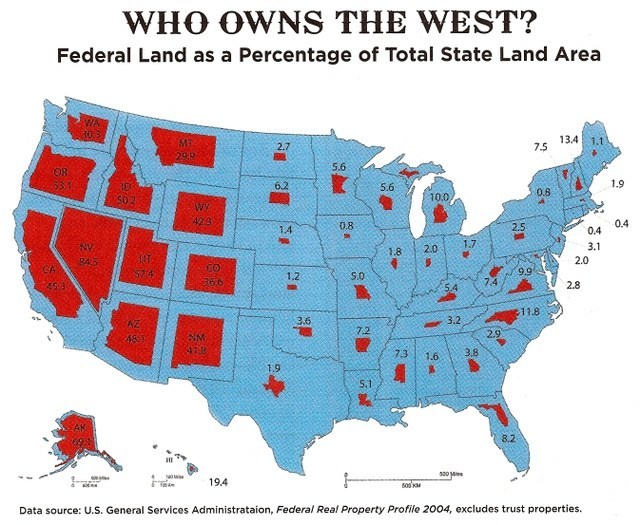

As we illustrated earlier, just a quick glance at the Federal Public Land Surface and Subsurface map on the back cover of this book tells a story of gross imbalance. All of that white area in the eastern two-thirds of the country is land that was restored to those States as Congress was obliged to do in its State Enabling Act Trust Compacts with those states. The State Enabling Act trust Compacts with the Western States, where you see all of that red land, retained by the federal government to this day, were exactly the same as those with the Eastern two-thirds of the States. So what is the difference in the way Congress fulfilled its obligations under the Enabling Acts between the Eastern States and the Western States?

ANSWER: The attitude of the federal government toward the States as the federal government grew and drew power to itself at the expense of the States.

This statement is easily proved by a look at the historical and legislative record. Those to the left on the political spectrum began to take power in the federal government, leaving an imbalance in Congress’ approach to its duties under the Constitution. Around the time the Western States had been admitted to the Union, and Congress was obliged under the State Enabling Act Trust Compacts to reincorporate their ceded lands to the States, as it had already done for the Eastern States, Congress simply decided to retain its own control over all of those lands, using them for members’ own political and social engineering purposes.

Today, when I attend debates about returning the Western States’ land to them, the opposition I encounter is still made up of the same kinds of people and organizations: ‘progressives’ who tell us how much better bureaucrats in Washington, D.C. can manage our land than we can; green extremists who want to keep humans off of as much land as possible; and anti-capitalists who incessantly fight to prevent us from extracting oil, gas, minerals and timber from the lands. We all realize that each of these groups to the left on the political spectrum has its political and social agenda, but their policies have an abhorrent effect on the balance of power between local people and federal bureaucracies, the balance of human harmony with nature, and the balance between using our natural resources to provide work and capital for our citizens and leaving our lands completely untouched. There is no balance, when extremist stances are given priority.

Don’t let my generalization of the types of people who oppose the Western States on this issue give you the wrong idea about me and my personal background. I grew up in a very conservation oriented family and hold strong conservation values. My father was a Forest Ranger for his entire career, spending 30 years in the U.S. Forest Service, obtaining his Master’s Degree in Range Management and devoting his professional life to the preservation of the Western forestlands. From the time I could walk I spent many of my days and years by his side, walking through the woods and scrub, learning firsthand about the ecology of our Western States and how we are stewards of nature. I learned all about the delicate balance between living with nature, and over-exploiting it to the point of destruction. I also watched as my father’s hopes and aspirations for the Western lands and wildlife were dashed on the rocks of federal mismanagement and incompetence at bureaucratic levels. The federal government’s simplistic, unenlightened, centralized, one-size-fits-all top-down bureaucratic policies allowed the bark beetle to devastate Utah’s forests. Due to the imbalance that has occurred between the federal government bureaucracies and the states, the federal government’s policies and incompetence have destroyed wildlife, forests and hundreds of thousands of acres of land, culminating in the closing of parks and recreation areas, and the abandonment of feral horse herds and other animals, and the locking out of millions of acres of land, and so on.

On Equal Footing

What’s wrong with the federal government retaining most of the land contained within the Western States? Under the Constitution, every new State was to be “admitted into the Union on an equal footing with the original States.” The Doctrine of Equal Footing is based on Article IV, Section 3, Clause 1 of the U.S. Constitution, which says:

New States may be admitted by the Congress into this Union; but no new State shall be formed or erected within the Jurisdiction of any other State; nor any State be formed by the Junction of two or more States, or Parts of States, without the Consent of the Legislatures of the States concerned as well as of the Congress.

Additionally, since the admission of Tennessee in 1796, Congress has included in each State’s act of admission a clause providing that the State enters the Union “on an equal footing with the original States in all respects whatever.”

The doctrine of equal footing originated in the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, which specifically addressed the issue of lands within the States. First, Article II is the equivalent of Articles IX and X of our current Bill of Rights:

ARTICLE II—“Each state retains its sovereignty, freedom, and independence, and every power, jurisdiction, and right, which is not by this Confederation expressly delegated to the United States, in Congress assembled.”

By this Article, the States jealously guarded their independent sovereignty. There was no intent to give up to a central “union” any more power of jurisdiction than was thought absolutely necessary. (STATEHOOD, 23)

ARTICLE IX—“. . . no State shall be deprived of territory for the benefit of the United States.”

Could it be any clearer? Under these Articles, no “forests,” for example, could be created within any State by the confederacy of States under the pretense of “national benefit,” nor could any national exigency be cited as justification for occupation of any land within any State without the consent of the affected State. (Ibid.)

At a debate on the subject, an opponent of States’ Land Rights will simply point to the Enabling Act clause where the State cedes its lands to the federal government, and tell you that’s the end of the discussion. I hear it from them every time. The problem with that argument is that nearly all State Enabling Compacts contain that same language, including the Eastern States, and a quick glance at the Federal Lands map on the back cover informs us that the transfer of lands to the federal government was only temporary, as a tool to clear all possible claims against the title of the land, to be followed by the release of those lands back to the States, or to private landholders who would then pay property taxes to the States.

George Washington wrote, “It rests with the states to determine the extent of territory over which the federal will exercise sovereign jurisdiction.” (The Writings of George Washington, 1745-1799, John C. Fitzpatrick, Editor, vol 32) Under the Enclave Clause, the federal government may indeed offer to purchase land from the various States for its own purposes, and if the State Legislature and Executive agree to the purchase, the federal government may establish a military base or other facility on that land. That land so purchased comes under the jurisdiction of the federal government, and Congress is given authority under the Constitution to deal with that land as it sees fit. Lands temporarily ceded to Congress as part of a State’s admission, however, never fall under the general Congressional authorizations under the Constitution, except to the extent that Congress must “dispose” of the lands as provided under the “trust” created by the Enabling Act Compact.

Breaking Trust

A trust is a legal device used to temporarily deposit property into the hands of a third party, who is charged with faithfully disposing of the property of the trust according to the written instructions of the person or entity establishing the trust. If you put your home title, stocks and bonds into a trust that will produce income for your children for the next 30 years, then be liquidated and the proceeds dispersed equally to your grandchildren, the trustee MUST do what you have instructed, or be found on the wrong end of a serious criminal statute. That is how trusts work—and because they are backed up by law, the “trust” aspect rarely comes into question—‘trust’ could be used interchangeably with ‘must.’ The trustee simply MUST follow the terms of the trust, or there are serious legal consequences, in which case the replacement trustee MUST fulfill the terms of the trust when the original trustee has been relieved of duties.

When the United States was first setting up its method of converting territories and other western lands into States, the Congress adopted the Resolution of October 10, 1780, thus committing itself to certain actions with respect to any lands that might be ceded to it by the various States:

(1) “Resolved, That the unappropriated lands that may be ceded or relinquished to the United States, by any particular states, pursuant to the recommendation of Congress of the 6 day of September last, shall be granted and disposed of for the common benefit of all the United States that shall be members of the federal union, (2) and be settled and formed into distinct republican states, (3) which shall become members of the federal union, and have the same rights of sovereignty, freedom and independence, as the other states: that each state which shall be so formed shall contain a suitable extent of territory, not less than one hundred nor more than one hundred and fifty miles square, or as near thereto as circumstances will admit: and that upon such cession being made by any State and approved and accepted by Congress, (4) the United States shall guaranty the remaining territory of the said States respectively. . . . (5) That the said lands shall be granted and settled at such times and under such regulations as shall hereafter be agreed on by the United States in Congress assembled, or any nine or more of them . . . .

This was the first ironclad commitment of Congress to dispose of the lands ceded to it for the creation of future states. It is unambiguous that a) all land so ceded to the U.S. would be “disposed of” by Congress, and that 2) each future State created out of this ceded land would “have the same rights of sovereignty, freedom and independence, as the other states.”

Therefore, all land being deposited into trust in the hands of the Congress was expected to be disposed of in the creation of new States, and Congress extinguishing the federal title therein, and each new State entering on an equal footing with the earlier States. In 1833, the Congress attempted to modify its duties under these trusts by passing The Land Bill. President Jackson vetoed the bill, and chastised Congress for attempting to usurp authority it did not possess, and abrogate its trustee duties to the States. President Jackson wrote:

These solemn compacts, invited by Congress in a resolution declaring the purposes to which the proceeds of these public lands should be applied, originating before the Constitution, and forming the basis on which it was made, bound the United States to a particular course of policy in relation to them by ties as strong as can be invented to secure the faith of nations.

In other words, President Jackson was telling Congress that it had no authority under the Constitution to abrogate its obligations arising under these Trust Compacts it had created to entice the People of States and Territories to cede land for the purposes of admission as States into the Union. President Jackson further explained:

The Constitution . . . did not delegate to Congress the power to abrogate these compacts, on the contrary, by declaring that nothing in it “shall be so construed as to prejudice any claims of the United Sates, or of any particular State,” it virtually provides that these compacts, and the rights they secure, shall remain untouched by the Legislative power which shall make all “needful rules and regulations” for carrying them into effect. All beyond this would seem to be an assumption of undelegated power.

I invite everyone to read the entire text of President Jackson’s Land Bill Veto Message, of December 4, 1833, because it so thoroughly explains the issues involved in the federal government’s duties over temporarily ceded lands to the federal government. The entire text can be found online.

By the time the State of Utah was admitted into the Union in 1896, the specific language of its 1894 Enabling Act had been used and recycled for decades to admit several other states, including Ohio in 1802, Louisiana in 1811, Mississippi in 1817, Alabama in 1819, Michigan in 1836, Arkansas in 1836, Wisconsin in 1846, Minnesota in 1847, and California in 1850. Each Enabling Act Trust Compact required the proposed State to relinquish and “forever disclaim” all right and title to its land in favor of the United States, followed then by the duty of Congress to “dispose” of or “extinguish” its temporary title in that land as part of its trusteeship. Following is the exact Utah Enabling Act language:

Second. That the people inhabiting said proposed State to agree and declare that they forever disclaim all right and title to the unappropriated public lands lying within the boundaries thereof; and to all lands lying within said limits owned or held by any Indian or Indian tribes; and that until the title thereto shall have been extinguished by the United States, the same shall be and remain subject to the disposition of the United States, . . . [Relevant portions of the Utah Enabling Act are attached in the back of this work as Appendix A]

Again referring to the Federal Lands map, we can see that the Congress indeed fulfilled the terms of the Trust Compacts with all of those States in the eastern two-thirds of the country, including all of the states admitted in the Nineteenth Century enumerated above. The only exceptions are the Western States.

On January 4, 1896, President Cleveland executed the proclamation designating Utah as a State, on an equal footing with the other States of the Union.

Shortly thereafter, we began to see a change in the attitude of Congress regarding the lands temporarily ceded in Enabling Acts at the time of admission. In 1905, the National Forest Service was created by combining the General Land Office (the agency created for the purpose of disposing of the ‘public’ land) and the Division of Forestry. Federal agencies, e.g. the Forest Service and Bureau of Reclamation, were then established for the purposes of managing vast tracts of “federal land” and western water resources. Land disposal policies began to be replaced with policies that retained the public lands in federal ownership. In a short span of time, some 234 million acres of ‘federal’ land, or nearly an eighth of the entire United States, were withdrawn from private entry. (Report of Utah’s Transfer of Public Lands Act, H.B. 148, p. 16.)

Utah patiently awaited the actions of the Congress, to fulfill its Constitutional trust mandate and extinguish its temporary possession of the land in Utah. By 1915 it was becoming apparent that the Democratically controlled Congress and Woodrow Wilson’s White House were dragging their feet on many issues of States’ rights, as well as minority rights, and the Utah Legislature proposed a Joint Memorial to the President and both houses of Congress, politely requesting that they execute their Constitutional duties and extinguish the government’s temporary title to Utah’s land. The letter first pointed out the requirements placed upon the federal government and the benefits to the earlier states of fulfilling those requirements:

Rejoicing in the growth and development, the power and prestige of the older states of the union, and recognizing that their advancement was made possible through the beneficent operation of a wise and most generous public land policy on the part of the government, the people of Utah view with alarm and apprehension the national tendency toward the curtailment of the former liberal policies in handling the public domain and disposing of the natural resources, as evidenced in the vast land withdrawals and the pending legislation, calculated to make our coal, our mineral and our water power resources chattels for government exploitation through a system of leasing.

The letter then made a gracious petition to release the land to the State of Utah so that it could enjoy the same benefits of all previous States:

In harmony with the spirit and letter of the land grants to the National government, in perpetuation of a policy that has done more to promote the general welfare than any other policy in our national life, and in conformity with the terms of our Enabling Act, we, the members of the Legislature of the State of Utah, memorialize the President and the Congress of the United States for the speedy return of the former liberal National attitude toward the public domain, and we call attention to the fact that the burden of State and local government in Utah is borne by the taxation of less than one-third the lands of the State, which alone is vested in private or corporate ownership, and we hereby earnestly urge a policy that will afford an opportunity to settle our lands and make use of our resources on terms of equality with the older states, to the benefit and upbuilding of the State and to the strength of the nation.

Of course, those who had seized power in Washington, D.C. had no intention of honoring the terms of the Trust Compact with Utah, or any other Western State. The petition was ignored, and the federal government began tying up major blocks of Western lands by designating new national parks, then wilderness areas, while selling leases for some minerals and oil on the land. In the case of Utah, those leases netted the State only 46 percent of the revenues that the Eastern States were receiving for their gas, mineral, timber and oil leases, and the number of leases allowed by the federal bureaucrats on Utah land were highly restricted.

Separate, But Equal?

There was a time when the federal government made a tepid attempt to make a partial transference of some desert surface land within the State of Utah, but the Democratic Governor at the time, George Dern, went to Congress and told them that their policies and proposal were wholly inadequate. In February of 1932, Dern appeared before the U.S. House Committee on the Public Lands to testify regarding legislation that proposed “to grant vacant, unreserved, unappropriated, nonmineral lands to accepting States.” The legislation would allow the States a 10 year period to determine whether to accept or reject the transfer of these unproductive surface lands, leaving the valuable minerals, gas and oil reserved to the federal government’s use. The Democrat excoriated the federal government for treating Utah and other Western States like adolescents, and told them that Utah did not want the lands on the proposed basis with “everything else taken out that is worth anything at all, so that we will have nothing but the skin of a squeezed lemon.” Good for him!

Since that time things have only gotten much worse for the Western States, and the federal government has dug in its heels, refusing to extinguish its temporary title in our State lands as required by the State Enabling Act Trust Compacts and the Constitution. In the 1960s and 1970s, environmental groups increasingly objected to aspects of federal management of public lands in the West and challenged the financial support extended to Western States and local governments by the federal government and the use of public lands for traditional activities such as grazing, mining, oil and gas exploration and production and timber harvesting. Environmentalists were joined by some eastern state representatives in Congress who sought to protect eastern industry from the threat of growing Western economies and those favoring federal budget cuts. (Ibid. p. 20)

In other words, Eastern States liberal members of the U.S. House and Senate were purposefully limiting Western States’ political power by limiting their access to their own in-state resources—keeping them poor and powerless.

The environmentalists also began to challenge federal support for water and transportation projects. They further called for legislation for the protection and conservation of “public resources.” In 1964, the Wilderness Act was passed. The National Historic Preservation Act followed in 1966. The Wild and Scenic Rivers Act and the National Trails System Act were enacted in 1968. The Endangered Species Conservation Act of 1969, the Wild and Free-roaming Horse and Burro Act in1971 and the Endangered Species Act in 1973 provided for protections to certain endangered species and the promulgation of new regulations (CFR) with which to comply. (Ibid. p. 20-21)

The National Environmental Policy Act (“NEPA”), enacted in 1969, required the study of environmental impacts resulting from federal actions and the receipt and consideration of public comment on any and all such actions. These legislative enactments culminated with the enactment by Congress of the Federal Forest and Rangeland Renewable Resources Planning Act of 1974, the National Forest Management Act of 1976 of the Federal Lands Policy and Management Act of 1976 (“FLPMA”). (Ibid. p. 21)

For those public lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), Congress’ FLPMA formally terminated the historic federal public lands policy of disposing of those lands pursuant to the Enabling Act Trust Compacts, in favor of a new formal federal land retention policy dictating that “the public lands be retained in Federal ownership.” The response of the Western States to the passage of FLPMA was a developing antagonism to federal actions, further fueled by the growing view of the federal government that Western needs had shifted away from traditional public land uses (farming, residential, harvesting, etc.), to purely recreation and environmental activities. (Ibid.)

Although Western States’ members of Congress have made various attempts to get the federal government to reverse its unilateral abandonment of its duty to divest itself of our Western lands, it has been to no avail. The federal courts have merely rubber-stamped Congress’ ability to extinguish title when it decides, not based on the precedents set in returning Eastern States’ land, and the expectations of the parties at the time of admission and creation of the Trust Compacts. So the clock ticks, and nothing is happening, and Utah and the other Western States suffer as a result.

Second-Class Citizens

Suffer, you ask? How do these states suffer? As we reviewed briefly above, the States in the Eastern two-thirds of the country utilize over 95 percent of their lands, collecting property taxes on privately owned lands and receiving 100 percent of the income from mineral, timber, gas and oil leases. This enables them to finance their public schools, among other things. Since Utah became a State she has continually struggled to fund public education. In fact, our state comes in dead last in the nation for per pupil educational funding. Our per pupil funding is $5,978 compared with the national average of $10,608, which averages in the other Western States, most of which are likewise strangled for funding for the same reason as Utah. States that enjoy the benefit of having received an extinguishment of federal title to their lands have much, much higher per pupil spending. New York, for instance, enjoys $19,552 per pupil spending. (States Spending the Most (and Least) on Education, Thomas C. Frohlich, 24/7 Wall Street, June 3, 2014)

Not only was Utah promised at the time of statehood—both expressly in its Enabling Act and impliedly by the historical federal policy of honoring its duty to dispose of the trust lands—that its lands would be returned to it or sold so Utah could collect property taxes on the land, the Utah Enabling Act specifically provided,

“That five per centum of the proceeds of the sales of public lands lying within said state, which shall be sold by the United States subsequent to the admission of said State into the Union . . . shall be paid to the said State, to be used as a permanent fund, the interest of which only shall be expended for the support of the common schools within said State.” (Section 9)

The land that the federal government was to dispose of by sale (“shall” according to the specific Enabling Act language) was to result in an educational trust fund, funded with 5 percent of the proceeds of the sales as the principle. Of course, as the federal government failed to follow up on its duties as the trustee of the temporarily ceded lands, no money for the educational trust fund was forthcoming, further damaging the children of the State of Utah.

As a result, the federal government came up with various revenue sharing schemes, payments in lieu of taxes (PILT), etc., amounting to a type of welfare handout system for those Western States relegated to the back of the federal bus, which only partially funds Utah’s educational system and county governments. The funds were considered less than half of what was needed in 1950, and there have been few annual, inflation, or cost-of-living increases in the fund since that time. In fact, PILT payments were removed from the main federal budget recently, and eventually attached to a Farm Bill and used as a negotiation pawn. Surely, no one can deny that Utah and most of the other Western States are treated as second-class citizens of the Union as a result of the federal failure to dispose of their lands as required.

Utah’s H.B. 148

To address the inequity of the federal government’s failure to extinguish title to two-thirds of the lands in the State of Utah, we in the Utah House of Representatives drafted House Bill 148, titled “Transfer of Public Lands Act” (TPLA), which I cosponsored with several other members of the House, and fully supported. The bill was passed by the State House and Senate, and signed by the governor, becoming law on March 23, 2012. The law sets out Utah’s demand that federal title in its land be extinguished pursuant to the U.S. Constitution and the Utah Enabling Act entered into by the State and the federal government at the time of Utah’s admission.

Of course, the TPLA proposes that all federally owned and managed parklands be permanently ceded to the federal government as National Parks. It also sets up a formal systematic transfer scheme, so that the transfers of land to the State are organized and the Utah State departments charged with relevant duties can adequately anticipate and meet the tasks. The TPLA also establishes the Utah Public Lands Commission to manage the multiple use and the sustainable yield of Utah’s abundant natural resources.

By receiving control of Utah’s lands, the State could solve all of its fiscal problems, especially the school funding problem, and greatly relieve the federal government of much of its burden with respect to managing Utah’s land. The federal departments and agencies charged with managing the State’s land, resources and wildlife find themselves constantly embroiled in horrendously costly litigation, which eats up most of their appropriated budgets—money that is not going toward managing the land and wildlife. This litigation is being churned out by the ream by the same groups we scrutinized earlier—environmentalists, anti-capitalists, and similar special interest groups who try to keep the land from being developed or even used by citizens, and who are opposed to using any natural resources like timber, minerals, oil or gas.

The fact that the federal government manages all of the Western States’ lands makes it an easy one-stop target for groups bent on getting their way through the filing of prolific litigation. If each of the States managed its own land, a special interest group would have to file 12 or 13 separate lawsuits per issue, at least one in each state court—possibly one in each affected county in every state. The cost of frivolous litigation would thereby switch to the special interest groups, greatly limiting the amount of damage they can do. As things stand, they simply file one lawsuit against the controlling federal agency, with the knowledge that federal agencies will cease all activity regarding the subject land until the litigated issues are finally resolved in the federal court system. Of course, federal courts are choked with this kind of litigation, and special interest groups know that each lawsuit will tie up the affected lands for several years, if not decades.

In other words, the very act of filing frivolous litigation nets the special interest groups what they seek, without the necessity of winning the litigation on the merits. The longer they string their frivolous cases along, the more they ‘win.’

If the control of these State lands was restored to the States, the financial burden of litigation would be placed on the special interest groups, who must battle their frivolous cases in state courts, with judges and jurors who are very close to the issues involved. The States’ costs of litigation would be much less than the federal government is paying because of the deterrence effect of placing the burdens of litigation where they belong—on the special interest groups.

Utah, like most of the affected Western States, is in a much better position to manage its resources than federal bureaucrats in Washington, D.C. The Bureaucratic method of top-down, one-size-fits-all management is destroying our lands and natural resources. What works in one area, does not necessarily work in another, but federal employees are restricted by the centralized regulations that have been promulgated by the truckload (CFR). If ever there were a clear example of why centralized government distanced from the problems of local people should be minimized, the management of Utah’s resources and wildlife is a perfect example. Employees of the various federal agencies tasked with managing Utah’s lands and resources have their hands tied not only by centralized, ineffective rules and regulations, but by constant budget shortfalls. The problem is not that the federal government does not allocate enough money, but that burgeoning federal bureaucracies and litigation costs rob the actual working employees of necessary personnel and resources.

As of this writing, our federal government is $18 trillion in debt, and 40 cents of every dollar it spends is borrowed, adding to the national debt every moment of every day and night. By the end of the current administration’s current term (December 2016), the national debt will be in excess of $20 trillion. Every day when Americans go to work, the first $1.4 billion they earn must go directly to the federal government just to pay the ‘interest’ on its debt. The federal government is so mismanaged that its continuation at its current pace is unsustainable. It WILL be crushed under its own bloated weight. It is not a question of if, but only when. The lands and resources of the State of Utah contain value in the trillions of dollars—one of our House members estimates minerals on federally retained lands in our state, Colorado and Wyoming at over $150 trillion, with a full one-third being located in Utah. See e.g., Knowledge and Courage: What the West Needs to Take Back Our Public Lands, Ken Ivory, Cascade Commentary. Those resources are being mismanaged and drained by the same government that is destroying our national economy and enslaving our children and their children with current overspending and debt. We do not need the federal government’s ‘help’ any longer in managing our own lands and resources.

States east of Colorado, which appropriately received a federal extinguishment of title in their lands, have resources and opportunities far beyond the reach of Utah and most similarly restricted Western States. We look around the country at states like North Dakota, where financial resources are abundant and educational spending has skyrocketed because they are free to utilize their land and natural resources, without the corruption and mismanagement that accompany federal management—of anything. The TPLA calls for a halt of the federal government’s mismanagement of Utah’s land and resources, and I want to continue working with Western States’ Governors and Legislative leaders until we obtain the lands and resources that are mandated by law and the Constitution to be released to us. The resources that are tied up and mismanaged by federal bureaucrats in the Western States are key to sparking local economies, and providing many billions of dollars in annual revenue to Washington, D.C.

Beyond just the financial reasons to return Western lands to the States, Americans have a very tangible health and environmental reason to do it sooner than later. Because the federal agencies are incapable of managing our forests, not only are we losing them to blight and wildfires, but millions of tons of carbon pollution are being pumped into our atmosphere when catastrophic fires annually light up the West. Where are the environmentalists when that happens? They’re driving their SUVs to protest rallies and ignoring the herculean damage to our lands and air quality created by their own policies.

Utah’s feral horse herds are likewise suffering under federal care. The wild horse problem in western Utah in Delta and Beaver Counties is devastating. The horses are neglected and wild, tearing up grazing land, and destroying livelihoods of local ranchers. The horses are starving to death, dying of disease. It is a horrific, inhumane mess, and those poor animals are suffering, because the feds have no budget to care for them.

In stark contrast, the State of Utah, as many other Western States, has done an exemplary job caring for its portions of the State’s forestlands and wildlife. Our deer, elk and bison populations have thrived under our care, and our state parks are second-to-none.

You may recall that the federal government has demonstrated that caring for our land and wildlife is less than a priority in its eyes. During the federal government impasse in 2013, the feds closed the national parks, to score political PR points in a budgetary saber-rattling contest, costing local businesses millions of dollars. We in State Government leadership reopened those parks with our own state funds—something the federal bureaucrats were unable to do.

The current administration has been legislating by executive fiat, and threatens to permanently tie up millions of acres of Western lands with the stroke of a pen, as other recent pro-centralized government administrations have done. All of this, of course, to further a political agenda—not to benefit the People of the Western States or the lands temporarily ceded to the federal government in State Enabling Act Trust Compacts.

Utah has been the model of excellence in utilizing what few resources we have available for responsible development as a State to provide for the care and welfare of our citizens, including our children. The fact that we have the least (approximately half) of the national average per pupil funding for children’s education, does not put us at the bottom of educational results. In fact, Utah’s children perform somewhere around the middle in most standard categories. Imagine what we could do with a normal per pupil spending budget—or a budget like an older State such as New York—nearly four times our per pupil budget. Utah currently ranks high in such areas as its high school graduation rate and parental employment, income and education levels. For example, last year Utah ranked 11th in the nation for children with at least one parent with a postsecondary degree, 1st in the nation for having the smallest difference in per pupil spending between the highest and lowest spending school districts, and 12th in the nation for its high school graduation rate. These results flow from our dedication to our State and its citizens, and our ability to roll up our sleeves and get a job done despite the obstacles placed before us by the federal government.

Utah’s TPLA is a comprehensive law that puts into place a sweeping mechanism for the State to receive the land that is still being held in trust by the U.S. Congress, and to transfer the management of the State’s lands and resources to local experts who have been educated, trained and prepared for the duties of self-management. I am hopeful that as American citizens become fed up with the disregard of States’ Rights and its incessant draw of power from the States to Washington, D.C., cooler heads will prevail and a more mainstream Congress (ideologically balanced) will execute its mandates under the Constitution and the State Enabling Act Trust Compacts and finally “dispose” of the State lands it is still holding in trust for the States, inuring to the benefit of the People of Utah, the Western States, and the entire nation.

By James Thompson. James holds a doctoral degree, and is a political commentator and professional ghostwriter.

Sponsored:

Would a BOOK with YOUR NAME on the cover launch you?

Be the one to get the speaking and media invitations.

I’ll help you write and publish your book in just 12 weeks. Get details, my fees, etc. in this FREE brochure:

Watch a 1 min VIDEO that explains my process:

Tired of Facebook? Check out Conservative-friendly social media. Join FREE today: PlanetUS

Watch this 30 sec. video about PlanetUS:

Leave a Reply