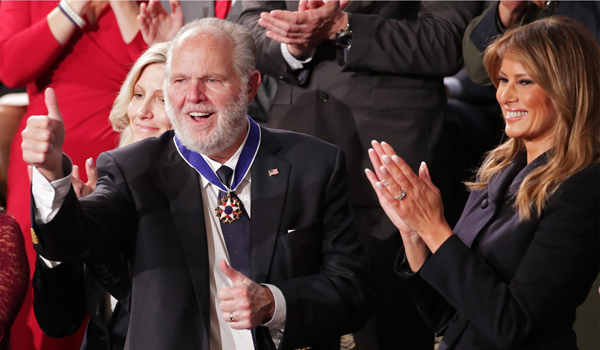

“I’m one of the luckiest people to be alive”

His ‘army of one,’ inspiring millions who’d been ignored, changed the political landscape.

Genius is often defined in myriad ways. One trusted criterion is the ability to do something extraordinary in a field where others could not — and doing something that perhaps will never be done again by anyone else.

By that measure, Rush Limbaugh certainly is the genius of talk radio, a genre in which he not merely excelled but that he also singlehandedly reinvented as something entirely different — and entirely more powerful and instrumental in American life — from what was imaginable pre-Limbaugh.

Even stranger still, his ascendance coincided with the presumed nadir of radio itself. It was supposedly a has-been, one-dimensional medium, long overshadowed by television. Even in the late 1980s, radio was about to be sentenced as obsolete in the ascendant cyber age of what would become Internet blogs, podcasts, streaming, and smartphone television.

Stranger still, Limbaugh has prospered through two generations and picked up millions of listeners who were not born when he first went national and who had no idea of why or how he had become a national presence.

He certainly did not capture new listeners by adjusting to the times. While tastes changed and the issues often metamorphosed, he did not. He remained conservative, commonsensical, and skeptical of Washington and those in it, as if he knew all the predictable thousand faces of the timeless progressive project, whose various manifestations reappear to mask a single ancient and predictable essence: the desire of a self-appointed group of elites to expand government in order to regiment the lives of ordinary people, allegedly to achieve greater mandated equality and social justice but more often to satisfy their own narcissistic will to power. It was Limbaugh who most prominently warned that lax immigration enforcement would soon lead to open calls for open borders, that worry about “global warming” would transform into calls to ban the internal combustion engine, and that the logical end of federal takeover of health care would be Medicare for All.

The Left — and many too who would later become the Never Trump Right — thought that Limbaugh’s worst moment finally came after Obama’s 2008 victory, during the post-election euphoria and just days before the January 2009 inauguration. It was a heady time, when the media would go on to declare soon-to-be Nobel laureate President Obama as, variously, a living “god” and “the smartest guy” ever to assume the presidency. His supporters often compared him to iconic wartime presidents such as FDR and Lincoln. Americans had been lectured on Obama’s divinity even as a candidate, and the evidence had ranged from the mundane of Platonically perfect creases in his trousers, to the telepathic ability to prompt spontaneous electrical impulses in the legs of cable television anchors.

In answer to Obama’s promise to fundamentally “transform America,” Limbaugh flat-out said he hoped that the new president would not succeed: “I hope Obama fails.” Outrage followed. Was Limbaugh rooting for the failure of America itself? In fact, he was worrying about how America might survive the first unabashedly progressive president in over 60 years, now empowered by an obsequious media, a House majority, a veto-proof Senate, and Supreme Court picks on the near horizon.

Limbaugh was the first voice to warn that what would soon follow the election was not the agenda that Obama sometimes disingenuously voiced on the campaign trail — Obama’s ruse of occasionally sounding concerned about illegal immigration, gay marriage, the spiraling debt, a rapid pullout from Iraq, and identity politics — but rather a move to the progressive hard-left.

What would ensue instead lined up with Obama’s senatorial voting record, his prior associations with the Reverend Jeremiah Wright, Bill Ayers, and Father Pfleger, and his occasional slips on the campaign trail: “I want you to argue with them and get in their face,” “If they bring a knife to the fight, we bring a knife,” and (in the pre-Netflix, pre–Martha Vineyard estate days), “I think when you spread the wealth around, it’s good for everybody.” Once elected, Obama was unbound. He lectured the nation about the wages of the West’s sin: the Crusades, America’s prior role in the world, and its own domestic woes. He instructed Americans on when it was the time to profit and when it was not, the point at which people should concede they had made enough money. And he listed the various reasons that he could not, as some anti-constitutional “king,” grant unconstitutional amnesties by fiat — before he went on to do just that.

Prior to Limbaugh’s national prominence, radio talk-show hosts were not shapers of national culture or politics. Even the few local and regional celebrity radio hosts had little power to influence issues of the day. While local talk radio was more conservative than liberal, it was hardly seen as traditional conservatives’ answer to the liberal biases of the major national newspapers, network evening news, and public radio and TV, much less the aristocratic pretensions of the Republican Beltway hierarchy.

So, what was inconceivable in 1988 was not just that any one person could leap from local prominence to national dominance, but that he could empower (rather than replace) his legions of radio subordinates. Far from making them irrelevant, Limbaugh energized talk-radio hosts. Once he became a national force, hundreds of others became far more effective conservative local and regional voices, partly through the art of emulation, partly through scheduling to lead in to or follow Limbaugh’s daily three-hour show, partly in the general renewed public interest in talk radio itself.

Call that coattails, or force multiplication, but in essence, Limbaugh redefined the genre as something more entertaining, more political, and yet more serious — an “army of one” antidote to the New York and Washington media corridor. How strange that after progressives achieved a monopoly in network news, public television and radio, the Internet conglomerates, Hollywood, and network prime-time programing, they sought to emulate Limbaugh by creating their own leftist version of national talk radio, Air America. Millions of dollars, dozens of talk-radio hosts, and Chapter 11 later, the venture collapsed in abject failure.

I wager that more Democrats listened to Limbaugh than to Air America, in the fashion of my late Democratic father, who used to sneak into my office on the farm and listen with me to Rush during the 1991 Gulf War.

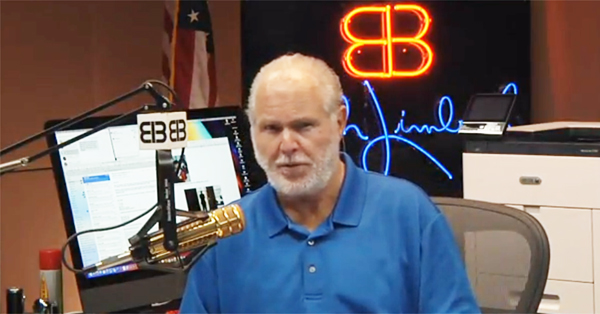

How did Limbaugh do it?

No one really knows because few have been able to duplicate his success, despite a number of gifted hosts who have tried. For all the criticism that Limbaugh was crass, over some 25,000 hours of the syndicated Limbaugh show, there were few embarrassments. And in cases where Limbaugh said something he regretted, he later apologized. He certainly could grow animated but seldom shouted and yelled. He talked about having talent “on loan from God” but could turn self-deprecatory and compliment callers for insights that he found original and noteworthy, saying, “I hadn’t thought of that.” He mocked identity politics but at work and in life often surrounded himself with talented people who were not white, and he seemed oblivious to any significance of that fact other than that he’d found friends and employees who were competent and whom he liked. He was a self-made multimillionaire many times over and proud of it, and yet felt and acted more comfortable with those of the Midwestern middle classes with whom he’d grown up.

Perhaps the best clue is that Limbaugh was never just a talk-show host at all. Or rather, he redefined the talk-radio three-hour format into something far more expansive than the critical arts of editorializing and answering impromptu listeners’ calls. In his prime role as unyielding conservative explicator of the daily news without the filters of the Washington and New York commentariat, he combined the jobs of entertainer, stand-up comedian, psychologist, impressionist, satirist, provocateur, therapist, and listener to the nation.

Yet ultimately his audience listened because he differentiated between two worlds. On one hand, he saw, with a skeptic’s eye, the cosmos of progressive and liberal translators who selectively edit the day’s events and massage their supposed importance to Americans, to present the news in line with liberals’ preconceived agendas — under the guise that such reporting was beyond reproach as professional, disinterested, and entirely based in facts. Limbaugh exploded all those pretenses.

But he also saw the other world that was never reported. He did not claim to be a traditional journalist or even an opinion journalist. Instead, he proudly assumed the mantle and collective voice of a conservative Everyman. Or maybe, more dramatically, his listeners saw him as an atoll of traditional sanity in a turbulent sea of postmodern madness. His forte was explaining why nominal conservatives were infected with a fatal virus of wanting to be liked by the “mainstream media” and the cultural elite — and thus often “grew” in office, moving leftward, as if they had become smarter and more sophisticated than those who had voted for them.

People tuned in because they knew in advance that Rush would not weaken or deviate, much less “transcend” them. There would be no faddish Limbaugh who renounced his prior personas and positions. So his listeners were reassured each day that they were not themselves crazy to express doubt about what the nation was told or instructed.

The New York Times story picked up by their local paper, the NPR segment they heard in the car, and the commentary of the ABC, CBS, or NBC evening news anchors were rarely if at all the whole truth and anything but the truth. Limbaugh reminded them that what was purportedly the news was increasingly the output of a rather narrow slice of cocooned America between Washington, D.C., and New York City, offered up by affluent progressives (the “drive-bys”) who had come to believe that the media’s role was not to report events per se, but to do so in a way that would not only educate the otherwise blinkered American masses but would also improve them morally and make them redeemable spiritually.

Limbaugh did all that, day in and day out, without any sense of monotony or boredom, but with almost adolescent energy and excitement about just talking to America each day. He never dialed it in. And his audience knew it.

Limbaugh himself knew his listeners, not just by class or locale, but through a shared skepticism about the values of coastal America and its inability to show any correlation between proven excellence and an array of letters after one’s name or name-dropping on a résumé. Does anyone think that a professor of journalism, a Washington pundit, a network anchor, a Senate elder, a president, or even a late-night TV host could host 30 hours of the Limbaugh show without losing most of the audience?

He was the Midwestern college drop-out who had bounced around among jobs before he found his natural place. Through that experience, he posed an ancient Euripidean question, “What is wisdom?” The answer was found in many of his targets: academics, editorialists, celebrities, journalists, government functionaries, and politicos whose bromides Limbaugh made ridiculous, and he instructed millions on how and why their ideas made no sense in a real world beyond their enclaves. Rush was hated by the Left supposedly for his politically incorrect -isms and -ologies; in truth, it was because he so often made them look ridiculous.

Limbaugh sounded sane when giddy Stanford grad and Rhodes scholar Rachel Maddow enthused about Robert Mueller’s daily walls-are-closing-in bombshells — much as farmer and Cal Poly graduate Devin Nunes wrote the truth in his House Intelligence Committee majority report while Harvard Law graduate Adam Schiff’s nose grew in his minority-report reply, and in the way that supposedly idiotic wheeler-dealer Donald Trump energized the economy after Ivy League sophisticate Barack Obama said it would require a magic wand.

In response to Rush Limbaugh’s announcement that he has advanced lung cancer, millions voiced sympathy, support — and shock. Last week, millions asked, “What are Rush’s chances?” The correct answer might be, “Not good — if it was anyone but Rush.”

Yet one who can create national talk radio ex nihilo can similarly beat toxic malignancy. His listeners seemed worried not just over Rush’s health but about their own equally ominous future of the day’s events without him.

May that day be far off.

By Victor Davis Hanson, NRO contributor Victor Davis Hanson is the Martin and Illie Anderson Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution and the author, most recently, of The Case for Trump. @vdhanson

Sponsored:

Would a BOOK with YOUR NAME on the cover launch you?

Be the one to get the speaking and media invitations.

I’ll help you write and publish your book in just 12 weeks. Get details, my fees, etc. in this FREE brochure:

Watch a 1 min VIDEO that explains my process:

Leave a Reply