North Korea has again successfully put a satellite into orbit, demonstrating the same technology needed to launch an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) and showing that its long-range missile program is becoming increasingly reliable.

North Korea has again successfully put a satellite into orbit, demonstrating the same technology needed to launch an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) and showing that its long-range missile program is becoming increasingly reliable.

In 2015, the U.S. commanders of U.S. Forces Korea, Pacific Command, and North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) publicly assessed that North Korea has the ability to hit the United States with a nuclear weapon.

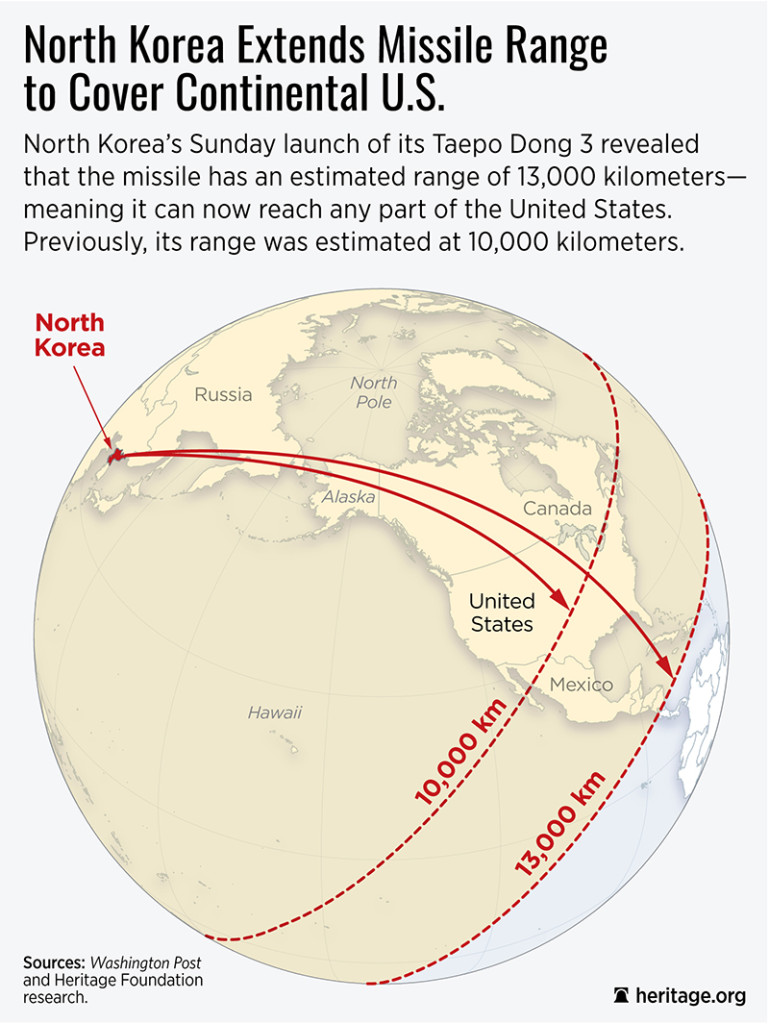

Preliminary assessments indicate that the satellite was approximately 450 pounds, twice as heavy a payload as the previous successful satellite launch in Dec. 2012, and that the missile may have a range of 13,000 km, an increase from the previous estimated 10,000 km range.

The longer range would put virtually the entire continental United States within range. Even at 10,000 km, approximately 38 percent of the United States, comprising 120 million people, was already within range.

It is clear that North Korea’s nuclear and missile tests are serious, irreparable violations of U.N. Security Council resolutions. This while the North Korean regime remains openly defiant of the international community despite countless attempts to reach a diplomatic resolution.

While the regime claims that the payload is merely a civilian “earth observation satellite,” several U.N. Security Council resolutions specifically preclude “any further launches” from North Korea “that use ballistic missile technology.” Both North Korea’s missile launch and its Jan. 6 nuclear test are unequivocal violations of U.N. resolutions and should be dealt with sternly.

U.S. officials privately commented last month that Washington was going for a “maximalist sanctions approach” in the U.N. but had again been stymied by Chinese obstructionism. Beijing continues to act like North Korea’s lawyer in the U.N. Security Council, trying to deflect additional sanctions and diverting blame onto U.S. “hostile policies.”

Beijing opposes stronger sanctions such as those that the U.N. imposed on Iran and induced Tehran back to the negotiating table. In response to North Korea’s nuclear test last month, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi advocated caution so that any new U.N. “resolution should not provoke new tension in the situation or destabilize the Korean Peninsula.” China reportedly rejected proposed sanctions aimed at reducing Chinese oil exports to North Korea and at preventing imports of mineral resources.

In parallel with U.N. Security Council debate, the U.S. Congress is finalizing legislation to impose tougher unilateral measures. The North Korean Sanctions Enforcement Act would expand U.S. authorities for targeted financial measures, impose penalties on secondary violators such as Chinese entities, and make enforcement of some provisions of U.S. law mandatory rather than discretionary.

The congressional action is spurred in part by lawmakers’ frustration over the Obama administration’s timid incrementalism of repeatedly hitting the snooze bar on enforcing U.S. laws and imposing more sanctions on North Korea.

Contrary to President Barack Obama’s assertion that North Korea is the “the most isolated, the most sanctioned, the most cut-off nation on Earth,” there is much more the United States can do to pressure North Korea, as I recommended in my recent congressional testimony.

Following the launch, the U.S. and South Korea jointly announced they would initiate formal discussions to deploy the THAAD ballistic missile defense system to South Korea. THAAD is more capable than any system South Korea has or will have for decades. It would provide more effective interception at greater altitude and distance than South Korea’s Patriot-2/3 systems. Previously, Seoul had been reticent to publicly discuss the deployment due to Chinese pressure and economic blackmail.

Chinese Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs Liu Zhenmin called in the South Korean ambassador to Beijing to formally lodge a complaint about U.S. and South Korea discussions of THAAD. Russia also opposes the deployment of the defense system, asserting that it would be contrary to “peace and stability in northeast Asia.” Both nations predictably are more critical of defensive allied responses than to the provocative North Korean behavior that triggered them. Contrary to Chinese and Russian claims, THAAD would not impact their security interests. THAAD, while effective against North Korean missiles, could not intercept Chinese or Russian missiles.

South Korea should also sever its involvement in the Kaesong joint economic venture with North Korea. The experiment has failed in its original objectives to curb North Korea’s aggressive behavior and induce economic and political reform. Kim Jong-un has shown himself to be ever more repressive than his predecessors and has embarked on a series of highly provocative and dangerous actions raising the risk of further escalation and military clashes. South Korea’s involvement funnels $100 million to the regime each year, undermining the effectiveness of U.S. and international sanctions.

It is time for the United States and its allies to impose stronger sanctions and to beef up security against the growing North Korean military threat.

By Bruce Klingner, a senior research fellow for Northeast Asia at The Heritage Foundation’s Asian Studies Center.

Leave a Reply