The Myth of Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings

The Myth of Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings

The sexual relationship lives on in books and film, despite a lack of verifiable evidence.

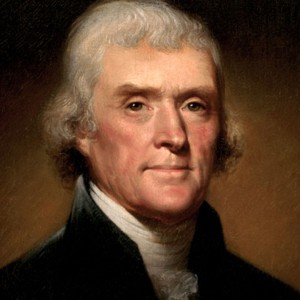

Thomas Jefferson has long been celebrated in America as the principal author of the Declaration of Independence. But his iconic status has diminished in recent years thanks to a widespread belief that he fathered a child by Sally Hemings, his enslaved servant.

In reality, the 1998 DNA tests alleged to prove this did not involve genetic material from Thomas Jefferson. All they established was that one of more than two dozen Jefferson males probably fathered Sally Hemings’s youngest son, Eston. And there is good reason to believe that at least seven Jefferson men (including the president) were at Monticello when Eston was conceived in the summer of 1807.

Allegations that the “oral history” of Sally’s descendants identified the president as the father of all of Sally’s children are also incorrect. Eston’s descendants repeatedly acknowledged—before and after the DNA tests—that as children they were told they were not descendants of Thomas Jefferson but rather of an “uncle.”

A more plausible candidate is Thomas Jefferson’s younger brother, known at Monticello as “Uncle Randolph.” An 1847 oral history titled “Memoirs of a Monticello Slave” noted that when Randolph visited Monticello, he would “come out among black people, play the fiddle and dance half the night.” Surviving letters establish that Randolph was invited to visit Monticello less than two weeks before the start of Eston’s likely conception window. Randolph had five sons in their teens and 20s who also carried Jefferson DNA.

The original version of the “Black Sal” story, published in the Richmond Recorder in September 1802, asserted that Sally’s eldest child was named “Tom.” Soon after Jefferson’s death, a former slave named Thomas Woodson claimed he was that “Tom” and had been sent to live with the Woodson family shortly after the story broke. But DNA tests of six descendants of three of Thomas Woodson’s sons proved that he could not have been the child of any Jefferson male.

Advocates of Thomas Jefferson’s paternity make a number of seemingly compelling arguments that upon close inspection turn out to be either false or easily explained. One is that Sally and her children received “extraordinary privileges” at Monticello. Most Jefferson scholars acknowledge there is no evidence of that.

ENLARGE

ENLARGE Jefferson did free Sally’s two youngest sons in his will. But he freed all but two of the sons and grandsons of Sally’s mother, Betty Hemings, and Sally’s sons received the worst treatment among those freed. Unlike others, they received no land, house, tools or money. Sally herself was never legally freed.

The claim that Thomas Jefferson had a sexual relationship with Sally Hemings began with James Thomson Callender, a notorious journalist and scandalmonger. Callender had demanded that Jefferson, who was elected president in 1800, appoint him postmaster of Richmond, Va. At one point during the summer of 1802, Callendar shouted from in front of the White House, “Sir, you know that by lying [in press attacks on President John Adams] I made you President!”

When Jefferson refused to make the appointment, Callender promised “ten thousand fold vengeance” and wrote a series of articles denouncing Jefferson as a French agent and an atheist. When those charges had no effect, he insisted that the president had taken a young slave girl to be his “concubine” while in Paris during the late 1780s. At the time, Sally attended to Jefferson’s young daughters, who lived in a Catholic boarding school across town in Paris that had servants’ quarters. She didn’t live at the Jefferson residence.

Both John Adams and Alexander Hamilton—political rivals of Jefferson’s at the time—rejected Callender’s charges, because they knew Jefferson’s character and had bitter personal experiences with Callender’s lies.

The case against Jefferson was the subject of a yearlong examination by a group of 13 distinguished scholars, including historians Robert Ferrell (Indiana University) and Forrest McDonald (University of Alabama), as well as political scientists Harvey Mansfield (Harvard) and Jean Yarbrough (Bowdoin). Save for a mild dissent by historian Paul Rahe (now at Hillsdale College) the group concluded that the story is probably false. This Scholars Commission, which I chaired, published its findings in book form late last year.

The legend of a sexual relationship between Jefferson and one of his slaves lives on in books, novels, films and the popular imagination. But proof—or even much verifiable evidence supporting it—is lacking.

Mr. Turner, a professor at the University of Virginia, is editor of “The Jefferson-Hemings Controversy: Report of the Scholars Commission” (Carolina Academic Press, 2011).

Leave a Reply